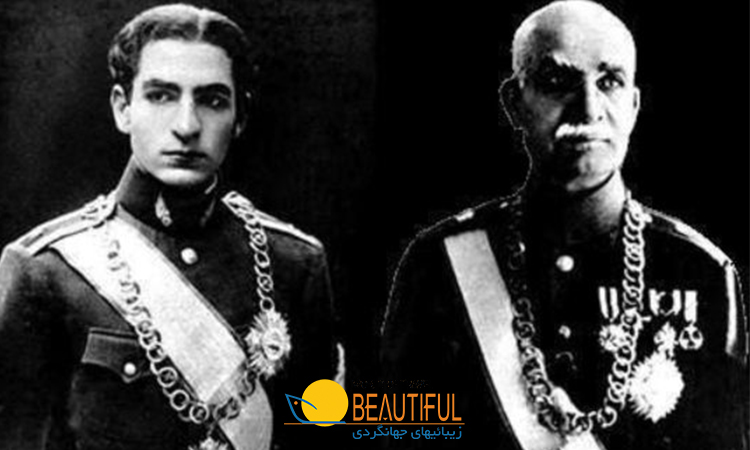

The founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, Reza Khan Mir Panj, was born on March 15, 1877, in the village of Alasht in the Savadkuh district of Mazandaran Province. Shortly after his birth, his father passed away, and his uncle, Colonel Nasrollah Khan, became his guardian. Reza Khan began his military career at the age of fifteen, progressing through the ranks until he became a brigadier general (Mir Panj) in 1918 and later gained prominence in 1921.

The Fall of the Qajar Dynasty

The political leader of the coup was Seyyed Zia’eddin Tabatabai, while Reza Khan acted as the military leader. Reza Khan, then the commander of the Cossack Brigade in Hamadan, entered Tehran with his forces on February 21, 1921, declared martial law, and seized control of government institutions, including the ministries and the telegraph office.

Ahmad Shah of the Qajar dynasty, under pressure from the coup plotters, appointed Seyyed Zia’eddin as Prime Minister and granted Reza Khan the title of "Sardar Sepah" (commander of the armed forces).

Minister of War

On May 4, 1921, Reza Khan was appointed Minister of War. During his tenure, he demonstrated decisiveness and restored security to the country, which had been plagued by crises resulting from World War I, the decline of the Qajar dynasty, and other internal and external challenges. Despite opposition from parliamentarians like Modarres, Reza Khan’s resignation was withdrawn after an increase in public unrest.

Prime Ministership of Reza Khan

In 1923, Ahmad Shah appointed Sardar Sepah as Prime Minister before leaving for Europe. Inspired by the establishment of the Republic in Turkey, Iranian military leaders under Reza Khan's influence advocated for the transformation of Iran into a republic. However, facing opposition led by the clergy, Reza Khan abandoned the republican agenda.

By 1924, with the shah's inability to return due to unrest in Tehran and mounting influence within the armed forces, Reza Khan laid the groundwork for abolishing the Qajar dynasty. On October 31, the Iranian parliament declared the end of the Qajar dynasty, marking the ascendance of Reza Khan.

Reza Shah Pahlavi

The Iranian parliament temporarily entrusted governance to Reza Khan and later formally amended the constitution, declaring him king of Iran on December 15, 1925. Reza Shah and his male descendants were granted hereditary rule over Iran.

Reza Shah’s Reforms

Reza Shah initiated significant reforms in the military, governance, and financial sectors to modernize the country. He built roads, established a railway network, and adopted a new educational system based on European models. Institutions such as the University of Tehran were founded, and students were sent abroad for higher education. Industrialization efforts, often supported by German experts, were undertaken.

Despite these advancements, many reforms disregarded Iran’s cultural and social fabric, leading to widespread dissatisfaction. In 1926, Reza Shah abolished capitulation agreements and restructured the judiciary system based on European practices. However, his authoritarian approach, lack of public support, and disregard for traditional institutions widened the gap between the people and the government.

The Clergy’s Opposition

Reza Shah’s modernization efforts clashed with religious leaders. The first major protest occurred in 1927 when women from the royal court visited the shrine of Fatimah Masumeh without veils, prompting demonstrations. Reza Shah responded harshly by deploying military forces to suppress the protesters.

A second protest emerged over the introduction of mandatory military service. Following negotiations with clerics in Qom, some concessions were made, temporarily calming tensions.

Assassination of Seyyed Hasan Modarres

In 1928, Seyyed Hasan Modarres, a prominent cleric and political figure, was arrested and eventually assassinated. Around the same time, the government implemented uniform clothing laws and imposed restrictions on religious attire, requiring permits for clerical garments.

Policies from 1928 to 1939

Reza Shah adopted aggressive policies toward tribal groups, including disarmament campaigns and forced resettlements, leading to violent uprisings. In 1931, the D'Arcy oil concession was canceled, but a subsequent agreement with Britain in 1933 continued to favor foreign interests, fueling nationalist discontent.

In 1936, Reza Shah enforced compulsory unveiling for women and Western-style clothing for men, sparking the Goharshad Mosque uprising in Mashhad, which was brutally suppressed.

World War II and the Allied Invasion

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Reza Shah’s close ties with Germany drew the attention of Allied powers. Despite neutrality claims, Iran was invaded by British and Soviet forces in August 1941. Facing mounting pressure, Reza Shah abdicated on September 16, 1941, and went into exile. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, ascended the throne.

Mohammad Reza Shah

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (reigned 1941–1979) took over during a tumultuous period marked by occupation, political unrest, and economic challenges. Food shortages culminated in the 1942 "Bread Riot," further highlighting the government’s inability to address public grievances.

Nationalization of Oil

In the 14th parliamentary elections, political figures like Mohammad Mossadegh gained prominence. Mossadegh proposed legislation prohibiting foreign oil contracts, eventually leading to the nationalization of the oil industry.

Withdrawal of Soviet Forces

After World War II, Soviet troops refused to leave Iran, supporting separatist movements in Azerbaijan and Kurdistan. International pressure and military action by the Iranian army eventually restored territorial integrity by 1946.

Assassination Attempt on Mohammad Reza Shah

On February 4, 1949, an assassination attempt against Mohammad Reza Shah failed. The event led to a crackdown on the Tudeh Party, a leftist political group. The Shah consolidated power by forming the Senate and appointing loyalists, including Haj Ali Razmara, as Prime Minister.

Mohammad Mossadegh’s Premiership

The political crisis in Iran stemmed primarily from the people's demands for fair distribution of oil revenues, equitable sharing among all societal classes—particularly the underprivileged—free elections to limit the monarchy's excessive power, and other aspirations fueled by global freedom and justice movements post-World War II. These challenges posed a serious threat to the Pahlavi monarchy.

When Mohammad Reza Shah denied Mossadegh’s request to control the Ministry of War, Mossadegh resigned. However, the public demonstrations on July 21, 1952, forced the Shah to reinstate him as Prime Minister. Mossadegh retired numerous high-ranking military officials and successfully passed the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry. His government championed reforms in state affairs, freedom of speech and press, political party activity, and adherence to constitutional principles to curtail the Shah's power. However, his severance of political ties with Britain provoked opposition from both Britain and the U.S., leading to efforts to topple his government.

The Coup of August 19, 1953

Mossadegh’s administration faced significant internal and external conspiracies. Political factions, threatened by his policies, united with the Shah and the royal court, supported by British and American political, financial, and military efforts. On August 19, 1953, after failed coup attempts, a military coup supported by foreign powers overthrew Mossadegh. Riots targeted Mossadegh’s residence, National Front centers, free press offices, and government institutions. This marked the beginning of an era of absolute monarchy, with a government controlled by corrupt military officials and foreign-influenced politicians.

The coup's aftermath saw severe suppression of nationalist and freedom-seeking forces. Prominent figures like Dr. Hossein Fatemi were executed, and negotiations with Western powers led to the reestablishment of oil agreements favoring international consortia. This era entrenched censorship, suppression of political dissent, and reliance on Western policies during Mohammad Reza Shah's rule.

The Baghdad Pact

Following the 1953 coup, Iranian governments pursued closer relations with Western countries. In 1955, Iran joined the Baghdad Pact, a military alliance between Middle Eastern states and Britain, later supported by the U.S. Concurrently, oil agreements were restructured to secure Western interests, stabilizing the Pahlavi monarchy and reinforcing Mohammad Reza Shah's reliance on Western powers.

The Premiership of Eghbal, Sharif-Emami, and Amini

From 1957 to 1960, Manouchehr Eghbal’s premiership consolidated Iran’s political and economic dependence on the West and strengthened the Shah’s absolute monarchy. However, widespread corruption and dissatisfaction led to his resignation.

Briefly, Jafar Sharif-Emami and Ali Amini succeeded, with Amini’s tenure marked by U.S.-mandated reforms aimed at combating corruption. Despite his efforts, Shah's interference and resistance from political elites undermined reforms. The Shah, supported by U.S. assurances, dismissed Amini and appointed Asadollah Alam, curtailing political reform efforts.

The Premiership of Asadollah Alam

Asadollah Alam served as a loyal prime minister, further solidifying Mohammad Reza Shah’s authoritarian rule. His government introduced controversial reforms, including granting women voting rights and revising electoral laws, which faced strong opposition from religious leaders. Protests led by figures like Ayatollah Khomeini resulted in violent crackdowns, such as the 1963 attack on the Feyziyeh School.

Alam’s era saw heightened public discontent, culminating in the June 5, 1963 uprising, a significant moment in the history of Iran's political resistance. This period also set the stage for broader dissent against the Shah’s regime, leading to Ayatollah Khomeini’s eventual exile.

The Long Premiership of Amir-Abbas Hoveyda

From 1965 to 1977, Amir-Abbas Hoveyda's 13-year tenure reflected a period of relative stability but growing authoritarianism under Mohammad Reza Shah. Key developments included the establishment of the Rastakhiz Party in 1975, which mandated public membership and intensified public dissatisfaction. Hoveyda’s premiership coincided with growing economic disparities, political oppression, and the emergence of guerrilla movements challenging the Pahlavi regime.

Major protests, such as the 1978 Black Friday massacre, underscored escalating opposition to the Shah’s policies. Hoveyda’s resignation in 1977 marked the beginning of the Pahlavi dynasty's political decline.

The Final Governments of Sharif-Emami, Azhari, and Bakhtiar

As political unrest grew, three short-lived administrations—led by Sharif-Emami, Gholamreza Azhari, and Shapour Bakhtiar—failed to address the crisis. The Shah’s departure from Iran on January 16, 1979, marked the end of his reign. Ayatollah Khomeini’s return and subsequent leadership galvanized revolutionary forces.

The Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty

The Pahlavi dynasty’s fall culminated in the Iranian Revolution of 1979, ending 57 years of monarchic rule. Widespread political and social dissatisfaction, coupled with the Shah's authoritarianism and Western dependence, led to the dynasty's downfall. The revolution marked a historic turning point in 20th-century Iranian history, transforming Iran’s political landscape and ending the era of Reza Shah Pahlavi's modernization efforts and Mohammad Reza Shah’s rule.

Summary of the Monarchy in Iran

The history of monarchy in Iran spans thousands of years, from the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great to the end of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979. Each era of kingship contributed to shaping the country’s cultural, social, and political identity. While ancient kings like Darius and Xerxes left legacies of imperial grandeur, modern rulers such as Reza Shah and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi introduced reforms aimed at modernization, often facing challenges from internal and external forces.

Today, visitors to Iran can explore this rich history through ancient sites like Persepolis, the palaces of the Safavid and Qajar dynasties, and the modern architectural landmarks of the Pahlavi era. If you're intrigued by Iran's historical legacy, consider traveling with World of travel beautiful, which offers curated tours to immerse you in the country’s fascinating culture, history, and landscapes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are some must-visit historical sites in Iran?

Iran boasts numerous historical sites, including Persepolis, Golestan Palace in Tehran, and the tomb of Cyrus the Great in Pasargadae. Each location provides a glimpse into the country's rich royal past.

2. How can I travel to Iran and explore its heritage?

You can book a tour through travel agencies like World of travel beautiful, which specialize in cultural and historical tours. They offer tailored itineraries, covering major landmarks and less-explored gems.

3. What was the role of the Pahlavi dynasty in modernizing Iran?

The Pahlavi dynasty, particularly Reza Shah and Mohammad Reza Shah, focused on modernization through reforms in infrastructure, education, and industry, as well as the promotion of Western-style governance. However, their policies were often met with resistance from traditional and religious groups.

4. Is Iran safe for tourists interested in history and culture?

Yes, Iran is generally safe for tourists. It offers a warm and hospitable environment for visitors, especially those interested in its history and culture. Following travel guidelines and booking with reputable agencies like World of travel beautiful ensures a seamless experience.